Hackney transport strategy submission

Introduction

Hackney has a good record on transport since 2002 having generally focussed on well evidenced interventions. For example, a councillor scrutiny committee in 2003 identified 20 mph zones enforced by humps as a key intervention. All Hackney’s residential streets and many others have such interventions.

In the 2000s there were substantial improvements to the bus services, with the introduction of congestion charging, bus priority lanes and many new and improved routes. The borough’s streets were improved with controlled parking, better street cleaning, maintenance and enforcement. It already had a number of are wide road closure schemes introduced for various reasons.

Hackney became the first borough to actively clear advertising boards from pavements outside shops, remove railings and renew its street nameplate system with accessible nameplates. TfL followed its lead on these things. There were regeneration schemes at Shoreditch with the removal of the one-way system, pavement widening schemes at Dalston Kingsland and Church Street and the closure and improvement of the Narroway. Numerous opportunistic streets schemes and slower speed initiatives created liveable and safer neighbourhoods. Hackney had a huge repaving budget for many years. The borough had numerous area wide road closure schemes, now called LTNs. Part of the borough was in the congestion zone.

The 2011 census found far more people cycled in Hackney than any other London borough, doubling in the ten years since 2001. The highest increase in the UK. The borough has the highest cycle share of trips of any London borough and a greater proportion of female cyclists. Indeed there are more female cyclists in Hackney than most other boroughs have males.

Hackney is the most successful local authority in the UK in terms of active and sustainable travel. It has a better sustainable transport mix than often quoted comparable cities.

Hackney has only 13% of trips by car

Copenhagen has 35% car trips

In Amsterdam they drive a lot. 30% go by car.

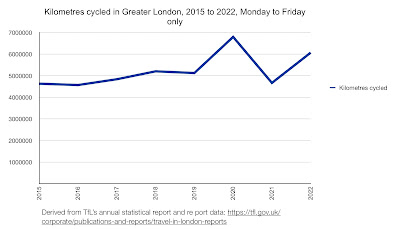

Post 2008, with Boris Johnson’s election, a lot of momentum was lost as the focus turned from traffic restraint, walking, cycling and buses to a single focus on cycling. Hackney avoided the worst of the blue cycle lane era, and made the most of cycle funding by, for example resisting a cycle superhighway on the A10. But like other boroughs has latterly wasted a lot of time and funding on cycle tracks. This has continued to date despite a lack of evidence on either road safety and growth in cycling. Indeed serious cycling casualties have risen in London, just about tracking the increase in cycle Kms since 2015.

The borough should refocus on a balanced strategy of restraining the car and improving ALL the sustainable modes, walk, cycle and bus.

Priorities

Much of the work and expenditure of local highway authorities seems to prioritise redesigning its streets. They are forever moving kerbs and utilities, spending a small fortune in the process. Lea Bridge Roundabout has been redesigned three times in recent decades and cost a small fortune each time. The most recent scheme a gross waste of £17m!

Hackney was at its best in transport when it prioritised its public realm and walking; recognised the role of the bus as residents most important means of travel beyond their local area and worked with a pragmatic cycling group towards more and safer cycling in Hackney’s context.

The first priority of any highway authority strategy should be the management and maintenance of the existing assets. Most importantly road and footway maintenance - a high priority for cyclists, when asked, is for a better road surface.

The second priority of any highway authority should be the management of its streets. But because this requires action by external agencies (the police) or parts of the council outside of the highways department, this gets left out of transport strategies in favour of the actions it can take. It is remarkable that parking operates seeming independently of Streetscene.

Roads policing, highways obstructions (overhanging hedges, advertising boards, chairs and tables, shop front trading, dumped LimeBikes etc.), parking management and de-cluttering the highway are all more or as important as redesigning the highway, but are in the purview of those outside the highways authority and so hardly get a mention in the Transport strategy.

The existing transport strategy provides for a hierarchy of users. This makes sense in general. It is absolutely the case that pedestrians and particularly disabled pedestrians should come at the top. There are many more walking trips and we are all pedestrians at some point. Pedestrians make up a big chunk of road casualties.

The almost single focus of Mayor’s Johnson and Khan on cyclists because they have managed to make so much fuss, despite being only 2% of trips and 8% of fatalities, is a tragic mistake and has cost lives and injuries.

Cycling is important for the city and so should be high up in its thinking, but so too are bus services. It cannot be right that cycling is prioritised above walking and bus services on bus routes in the manner that it has. The Balls Pond Road scheme is an example. It was dreamt up by Andrew Gilligan and has done nothing for cycle safety, indeed has worsened it, with most cyclist injuries at the junction of Kingsbury Road after implementation.

Nobody, it seems, cares about motorcyclists, but they are, by any measure the most vulnerable mode. Much more needs to be done for motorcyclists, but it is difficult for highways authorities as more roads policing is required to really address this I think. However, an understanding and empathy with their needs and the impact of carriageway narrowing is really important. They account for 30% of deaths in Hackney, twice that of cyclists, yet are very minor in terms of number of trips made. Do they get 30% of our road safety attention?

A Transport Strategy for Hackney

Create great city streets and public spaces for Hackney.

In 2004 Jan Gehl, the world’s foremost urbanist produced a blueprint to transform London to be a ‘fine city for people’. Hackney should again learn from that report and create and manage fine city streets for pedestrians to walk, rest and play as its priority.

Everyone should follow the rules

From ensuring hedges are cut and unlawful obstructions are removed, to waste not being dumped and the rules of the road are observed. Our streets should be actively managed to be safe and pleasant places for everyone. This will mean education, but must include enforcement from across the council and beyond. Not just Streetscene initiatives. The recent Hackney Road parking proposals were bizarre. The parking service should be part of the Streetscene function with the same objectives.

I never managed to get an overarching streets enforcement directorate, but their aught to be one.

Maintain what we have

The first responsibility of the highway authority should be to maintain its assets. Too much is spent on moving kerb lines and utilities for the next redesigned street whilst potholes and pavement trips remain unrepaired. Please prioritise good streets maintenance.

Restrain the private car

Area wide road closures of streets to through traffic is a good thing. But surely we can recognise the mistakes of recent implementation. Without considering the operation of main roads, particularly bus routes, further schemes will mean poorer bus services, congestion and avoidable antipathy.

Hackney, as its number one priority, should be to remove parked cars from its main streets implementing bus lanes where it can or wide inside lanes. Hackney Road is the example I use. I know its a Tower Hamlets Road, but Hackney recently added parking to our side of the street. Clearly the parking department needs signing up to parking restraint! Every bus route in Hackney should be a bus priority route with bus lanes added and parking replanned/removed.

Clearly motor vehicle restraint is difficult even in an inner London borough, but its an issue that can’t be shied away from. Congestion will worsen with untaxed, cheap electric mobility. The Mayor of London has made a mess of transport and so cannot be expected to win this argument, but other politicians need to. EV cars aren’t a solution to Hackney’s congestion problems and there is only so much that can be done without restraint. Roads pricing should be retained as a strategic policy objective and the arguments made for it.

Improve the sustainable modes

It is sad that one has to say this, but not everyone will cycle. Some just want to catch the bus or tube. Everyone wants to use the cities streets as a pedestrian.

Briefly, improving our city streets means clear, level and wide footways and creating places to linger. Over the years this is what Hackney has done well. There are many examples of fine city streets and places In Hackney.

The cycle is important and much can be done to enable more and safer cycling. But so too are bus services and walking. More and safer cycling need not be to the detriment of pedestrians or bus services. Buses should have priority on all the streets they use. Hackney Road, Amhurst Park Road, Balls Pond Road, Graham Road Dalston Lane, etc. should be prioritised for bus services by removing parking and where possible introducing bus lanes. Crossing the street for pedestrians remains important.

Cyclists generally like bus lanes, though some in the new cycling activism have an ideological position against them. They are being unrealistic.

Cycling has been enabled in Hackney by the implementation of area wide road closure schemes, parking controls and slower speed initiatives enforced by, side road treatments and speed tables, alongside bus priority on main roads. Hackney once took the view that all its streets should be cycling streets.

The idea of a small number of streets forming a grid was rejected.

Prioritising bike tracks at the expense of bus services is the height of stupidity, as we have seen over the last decade across London.

Road safety

It used to be the case that London’s road safety policies were guided by saving lives and injuries. There was a concept of ‘casualty savings’ per £. Since the cycle lobby intervened in the way it has road safety is dominated by ‘subjective safety’ and focussed on cycle safety. They think it as important to feel safe as actually improve safety!

The idea that feeling safe should be the objective of road safety interventions is bizarre and has backfired. We have our local example at Green Lanes where more cyclists have been injured since the cycle tracks than before they were installed. Hackney should remove these temporary tracks and halt its implementation of new tracks and focus on what works to save casualties.

Removing cycle tracks through bus stops should be a priority for the borough so that once again we can be proud to have a safe and accessible bus network for all.

Slower speed initiatives are known to save lives. Hackney has done well with its borough wide implementation of slower speed initiatives going back decades. Its priorities should be:

- upgrade speed pillows in our residential streets to humps - pillows don’t slow traffic

- to work with the police to introduce more roads policing and enforce the rules

- To upgrade side road treatments to ensure a good steep ramp up to the speed tables and to retrofit the Copenhagen crossings such as at Hilstowe Street

- Targeted engineering works at locations with a history of casualties.

The borough has a fine tradition of training youngsters to cycle and road safety education. Long may this continue.

Cycle tracks

Cycle tracks in busy urban streets have been touted as key to more and safer cycling. They are said to encourage older, younger, female and ethnic minority cyclists. This is a fallacy and was rejected by Hackney cycling advocates for many years for the following main reasons:

- They trap the cyclist too far to the left of the lane to properly turn right according to their training;

- they trap the straight-ahead cyclists too far to the left to avoid being hit by left turning motors. Both cycle and motor are competing for the same road space. The classic ‘fail to see’ collision hasn’t and won’t go away, nor will the provision of four seconds advance start. Fail to see left hooks have increased on some cycle tracks: See LCCs worst junction in London.

- cycle tracks are often complex, particularly the bi-directional tracks. Guidance often warns against them. TfL, bizarrely, puts bi-directional tracks in to mitigate the problems of single direction tracks- the safest streets have simple, understandable and self-explaining layout; all users should understand where to expect each other;

- Simon Christmas in his DfT commissioned report: Cycling, Safety and Sharing the Road: Qualitative Research with Cyclists and Other Road warns that ‘different cyclist have different needs’. Essentially designing infrastructure for one group is problematic for others;

- cycle tracks sterilise access to the kerb for those that need to deliver, load or board a vehicle.

Green Lanes and Balls Pond Road are good examples of these problems. Green Lanes record is poor. 36 months prior to the bike track 8 slight cyclist injuries occurred. Post implementation, in February 2021, 4 serious and 12 slight cyclist injuries occurred. This was predicted. On BPR, at the junction of Kingsbury Road, 7 casualties occurred post implementation in 2021 compared to one in the previous four years. See appendix.

The temporary plastic pole schemes need removin in short order and a plan to deal with the others made.

Active travel schemes and the disabled

Active travel schemes that route cyclists onto and through the pavement are hated by many pedestrians. Blurring the boundaries between wheeled vehicles and pedestrians on the pavement means some, particularly vulnerable pedestrians, will be deterred from walking. Blind people are increasingly unable to get around their locality. They are excluded from bus services they have previously used.

Blind people cannot see nor hear cycles at the chaotic places we now call floating bus stops. How can they cross these zebra crossings when cyclists won’t slow for them, let alone stop. It is not the case that these crossing are akin to conventional crossing- ask a blind person to explain!

Major schemes for Hackney

The reversion of the Victoria Park gyratory should be a major scheme in the next ten years.

The TfL network

TfL used to be a great advocate of restraining the private car, slower speeds and great city streets. They now no longer are. I suggest

- Hackney should try and persuade them to remove the uncontrolled parking on the roads they control. These are our strategic roads too.

- we should persuade them to up their enforcement of illegal waiting, etc.

- they revert the SN gyratory in a manner sensitive to its strategic and local purpose. Hackney has a good scheme. Will Norman’s intervention in the last scheme was tragic.

- It is crazy to close minor roads to through traffic and at the same time ban turning movements between the primary road network roads. They did that at Dalston Junction recently. This and other bans need revisiting.

- I really hope the road safety schemes for Shoreditch are sensible. I fear they won’t be. I suggested a green cycle phase at the A10/A1209 junction and only three lanes for Great Eastern Street along full two-way operation of the gyratory.

Appendix - From the TfL road safety dashboard